15. juli 2024 nyhet

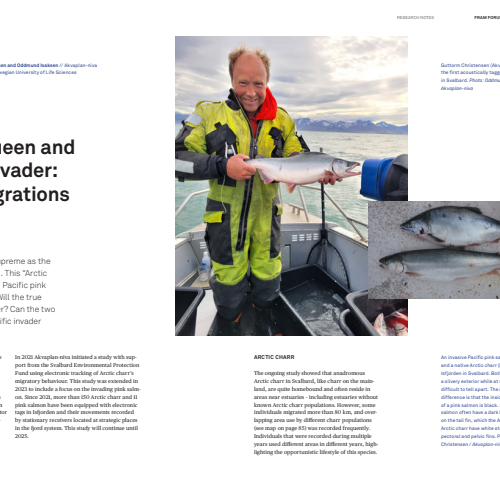

By Jenny Jensen, Guttorm Christensen, Eirik H Henriksen and Oddmund Isaksen (Akvaplan-niva) and Thrond O Haugen and Thor Bjørn Thorkildsen (Norwegian University of Life Sciences)

The Arctic charr long reigned supreme as the only freshwater fish in Svalbard. This “Arctic queen” must now compete with pink salmon invading the Atlantic Ocean after targeted releases in Russia. Will the true Arctic be too cold for the invader? Can the two species co-exist, or will the Pacific invader supplant the Arctic queen?

The anadromous Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) lives a marginal life in Svalbard. Anadromous fish alternate between fresh and salt water, feeding at sea and reproducing in fresh water, but Svalbard’s unpredictable freshwater runoffs restrict access to the nutrient-rich marine areas. Moreover, the Pacific pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) – a potential competitor – has recently invaded northern Norway including Svalbard. Arctic charr is in high demand by anglers, but knowledge on population size and harvesting patterns is scarce. All these factors make the species challenging to manage.

In 2021 Akvaplan-niva initiated a study with support from the Svalbard Environmental Protection Fund using electronic tracking of Arctic charr’s migratory behaviour. This study was extended in 2023 to include a focus on the invading pink salmon. Since 2021, more than 150 Arctic charr and 11 pink salmon have been equipped with electronic tags in Isfjorden and their movements recorded by stationary receivers located on strategic places in the fjord system. This study will continue until 2025.

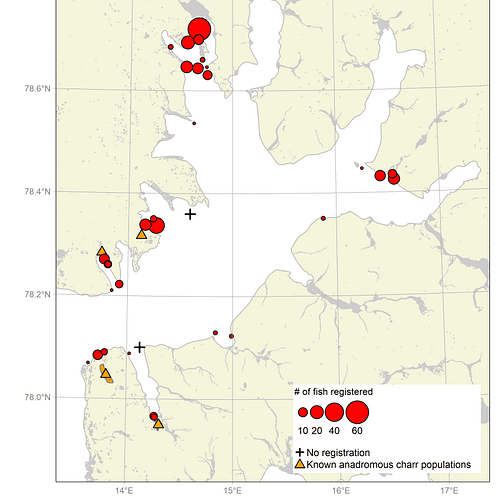

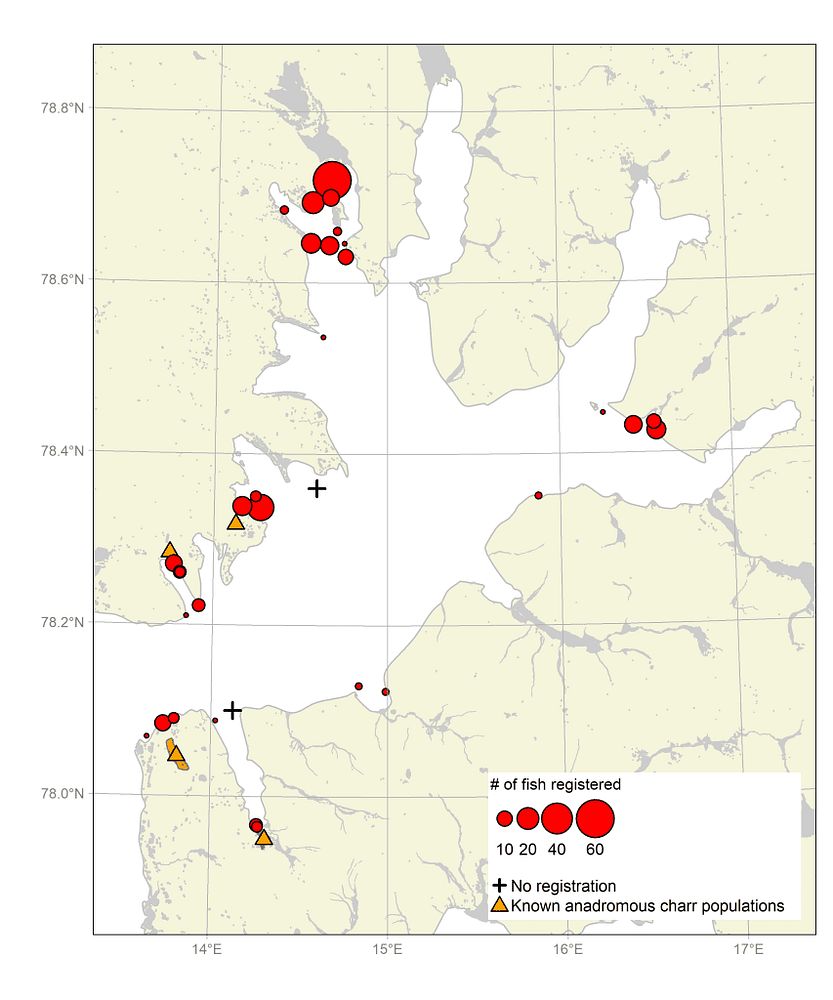

The number of tagged Arctic charr registered on acoustic receivers in Isfjorden in Svalbard. Acoustic receivers, placed on buoys moored as indicated by the circles on the map, registered and stored unique signals from individually tagged fish. The size of each circle indicates the number of tagged fish detected by the receivers during the study and gives a rough picture of area use amongst Arctic charr. Plus signs show the locations of receivers without detections. Documented anadromous Arctic charr populations are marked with triangles. Map: Eirik Haugstvedt Henriksen (Akvaplan-niva) and Benjamin Merkel (Norwegian Polar Institute).

Arctic charr

The ongoing study showed that anadromous Arctic charr in Svalbard, like charr on the mainland, are quite homebound and often reside in areas near estuaries – including estuaries without known Arctic charr populations (see map on p X). However, some individuals migrated more than 80 km, and overlapping area use by different charr populations was recorded frequently. Individuals that were recorded during multiple years used different areas in different years, highlighting the opportunistic lifestyle of this species. The fish were found almost exclusively between 0-3 metres depth. We also found that Arctic charr in Svalbard often reside in the estuary for about one week before returning to fresh water.

The timing of Arctic charr migration from freshwater to the sea most likely depends on ice conditions in lakes and rivers. In 2022, charr left the rivers during the first two weeks of June or earlier. By the end of July around 60% had returned to freshwater, with larger individuals returning first. Most rivers in Svalbard dry up during autumn, which makes the anadromous lifestyle of Arctic charr a risky endeavour, and may explain why larger, sexually mature individuals return early. The optimal migration strategy will most likely vary among years in this unpredictable environment.

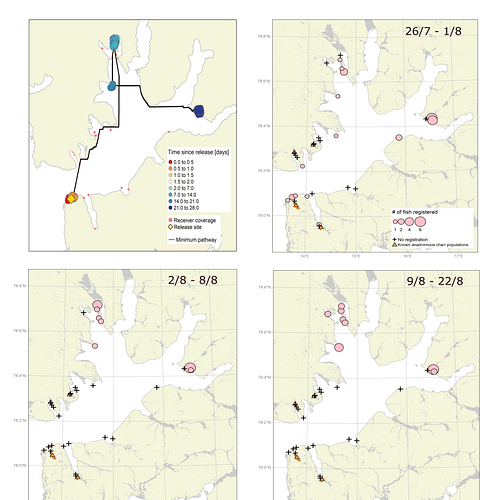

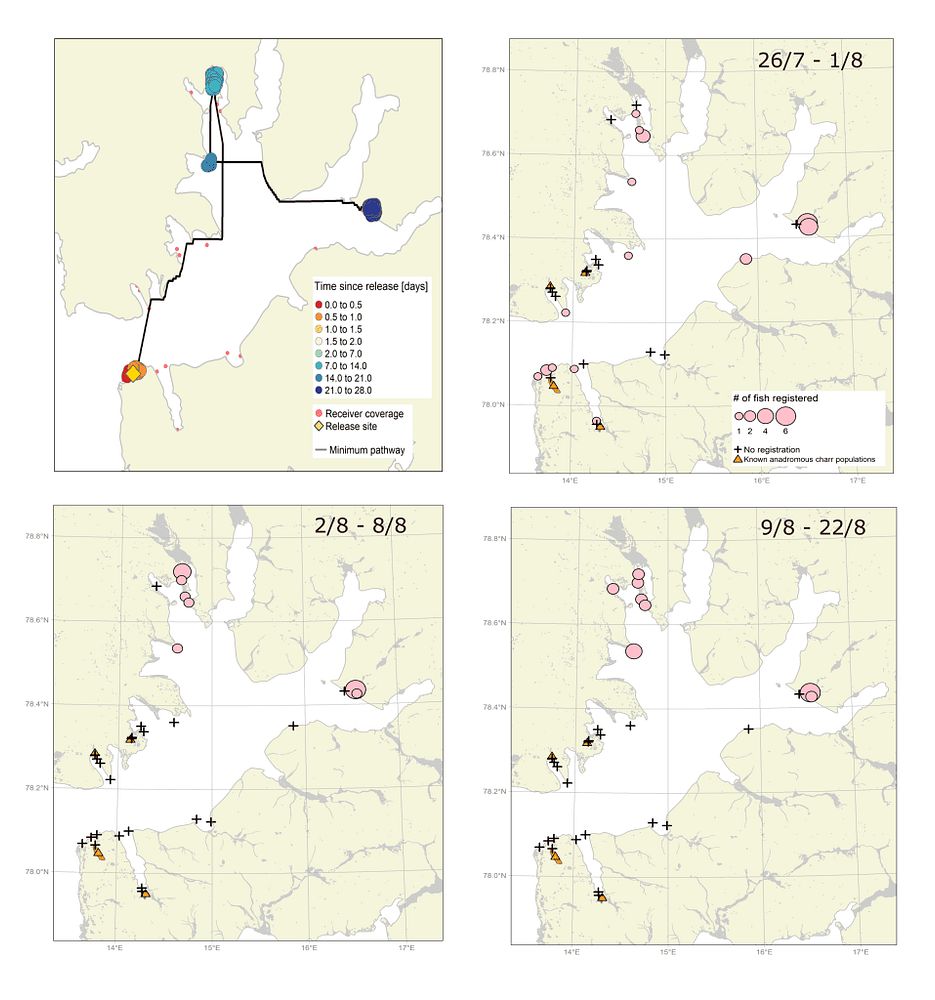

The movement of an individual pink salmon over time in Isfjorden (top left), and bubble diagrams showing the number of pink salmon recorded by the acoustic receivers in the first (top right), second (bottom left), and third and fourth (bottom right) week after tagging. Each bubble represents an acoustic receiver, and its size signals the number of different fish registered. Plus signs show the locations of receivers that detected no fish during the specified periods. Maps: Eirik Haugstvedt Henriksen / Akvaplan-niva and Benjamin Merkel / Norwegian Polar Institute.

Pink salmon

Pink salmon on mainland Norway typically enter rivers for spawning in late July/early August and spawn in mid-August. In Svalbard, however, pink salmon tagged at sea at the end of July were registered in the fjord or estuaries for on average 13 days. The tagged pink salmon in Svalbard thus stayed at sea later than the majority of their mainland counterparts. Six of the individuals tagged in Svalbard used large parts of Isfjorden after tagging (illustrated by #967), while the other five individuals remained near their estuarine tagging location. The tagged pink salmon ranged more widely over Isfjorden during the week after tagging than later in the season.

Our study so far indicates that Arctic charr and pink salmon have an overlap in fjord area use in Svalbard. They also have a known overlap in diet. Arctic ecosystems are sensitive to change, and climate warming together with random effects such as an introduced species may cause large disturbances. There is a strong need for careful monitoring, and this ongoing study is a first step towards understanding the impact of the recent pink salmon invasion in Svalbard. We hope our novel information on fjord migratory behaviour of anadromous Arctic charr and pink salmon can aid managers in protecting our northernmost freshwater fish species.

This article has previously been published in Fram Forum: https://framforum.com/2024/03/...